Via LA Times

Paul R. Williams designed buildings in a range of styles — including Spanish Revival and Modern — that have come to define the L.A. landscape.

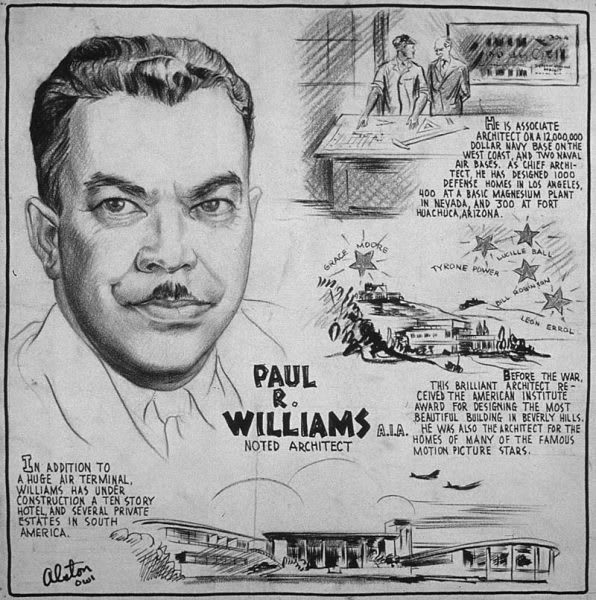

Buried beneath a weather report and an investigation into a regional planning commissioner, a brief news item appeared in The Times about the death on Jan. 23, 1980, of architect Paul Revere Williams at the age of 85. Three days later, the paper ran an obituary. That report was a bit more complete. It featured a photograph of Williams and ran through a handful of his achievements: He was the first Black architect to be admitted into the ranks of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and a wildly prolific designer who’d had a hand in designing well-known commercial and civic buildings (such as the Los Angeles County Courthouse), as well as graceful homes for celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, Barbara Stanwyck and Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. Yet his death was not treated as big news.

The modest obituary ran on page 22. In the immediate wake of Williams’ death, no glossy books of his work were published, much less a catalogue raisonné. Buildings he designed were torn down; others, remodeled beyond recognition. The work of an architect whose firm was responsible for thousands of structures in Southern California, who was name-checked in real estate ads as “world-famous,” who shaped L.A. through civic roles including a seat on the City Planning Commission — a position he assumed in 1921 at the tender age of 27 — was in danger of fading away. How times have changed.

In 2017, the AIA posthumously awarded Williams its prestigious Gold Medal. Last February, PBS aired the documentary, “Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story.” In the fall, artist Janna Ireland published the elegant photographic collection “Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View.” In November, HomeAdvisor, a home repair site, commissioned illustrator Ibrahim Rayintakath to draw 43 Williams homes.

Most significantly, last summer, USC and the Getty Research Institute announced that they had jointly acquired Williams’ archive — a trove of approximately 35,000 architectural plans and 10,000 original drawings, in addition to blueprints, hand-colored renderings, vintage photographs and correspondence. The acquisition will, for the first time, allow public access to the breadth of the architect’s work.

Los Angeles wouldn’t be Los Angeles without the hand of architect Paul R. Williams, whose handwriting graces the façade of the Beverly Hills Hotel.(Anna Higgie / For The Times)

Beverly Hills Hotel, Crescent Wing, 1940s, 9641 Sunset Blvd., Beverly Hills

No building channels the ebullience of Hollywood quite like the Beverly Hills Hotel. Williams didn’t design the hotel’s original Mission-style building (which was done by Elmer Grey). But he was responsible for various expansions, including the Modernist Crescent Wing — which juts out toward Sunset Boulevard and greets incoming visitors with a zingy sign crafted from Williams’ own handwriting. Architectural historian Alan Hess says that buildings such as Williams’ Beverly Hills Hotel addition mark a singular period of architectural design in Southern California that he calls “Late Moderne.” “It wasn’t for the most part influenced by the trends coming out of New York, the International Style,” Hess says. “It really emerged out of the West. It was interested in modern materials and lifestyle and being new and fresh, not relying on traditional design. They were very inventive about it.”

Williams’ granddaughter, Karen Elyse Hudson, who has been the steward of her grandfather’s papers, says the archive contains “the story of a man and his influence on the city.” That influence is formidable. Alongside architects such as Welton Becket and William Pereira, Williams helped give L.A. its look.

The renewed attention to Williams couldn’t come at a more critical time. At a moment in which violent white supremacy is ascendant, Williams’ buildings are a reminder that Black people not only helped build U.S. cities — they also designed them. “This is a very rare instance of maintaining memory,” says LeRonn P. Brooks, lead curator for the African American Art History Initiative at the Getty Research Institute. “African American archives are as vulnerable as the people themselves.”

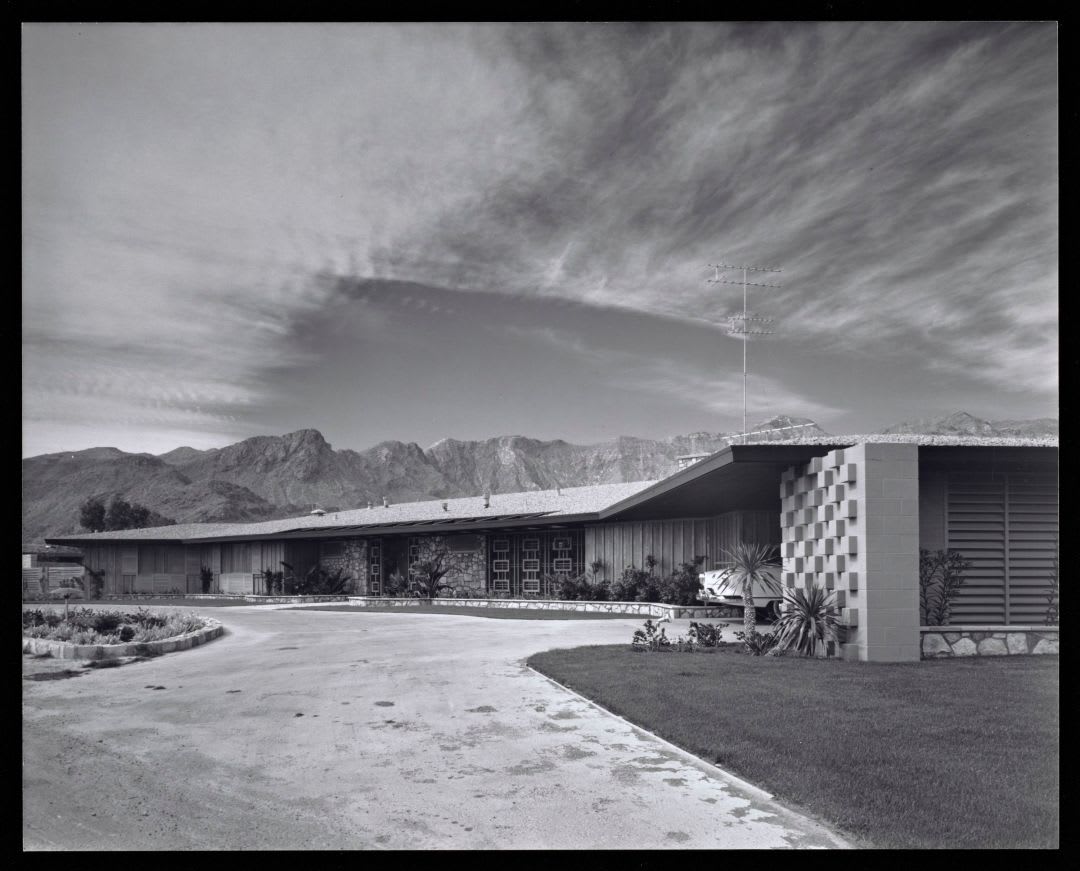

Paul R. Williams counted among his clients many Hollywood celebrities, including Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, for whom he designed this Modern house in Palm Springs in the 1950s.(Julius Shulman / J. Paul Getty Trust)

In fact, a piece of Williams’ archive has already been lost. Office paperwork from his studio was stored at a bank that went up in flames during the 1992 Los Angeles uprising. The fire did not, however, claim his architectural designs, as has been incorrectly reported over the years. They were at another location. The surviving documentation will help bring greater dimension to an architect whose sophistication as a designer is often overlooked by media reports that focus almost exclusively on his biography.

Without a doubt, it’s a compelling story: Born in Los Angeles in 1894, Williams was an orphan who doggedly pursued a career in architecture — despite active discouragement from his instructors — and went on to become the “architect to the stars.” All the while, he navigated the question of race in a city that, for much of his life, operated in a state of de facto segregation. He designed homes in neighborhoods where restrictive covenants barred him from living; he helped expand hotels that would not admit him as a guest.

One widely shared anecdote is that Williams taught himself to draw upside down so that nervous white clients wouldn’t have to sit alongside him. (The reality of how he deployed that skill may have been more nuanced: In a 1963 piece Williams wrote for Ebony, he described it as “a gimmick which still intrigues a client.”)

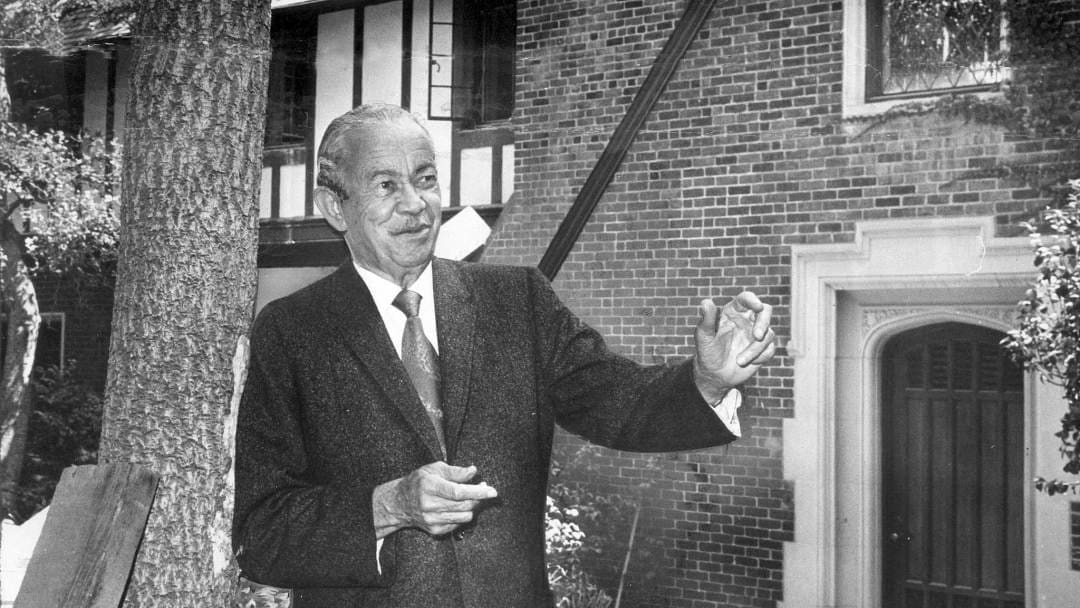

Architect Paul Revere Williams in 1970, standing before a Tudor mansion he designed in 1928. (Los Angeles Times)

Williams’ prominent status made him, in many ways, an insider. But as a Black man in architecture, he would always remain an outsider. To this day, the field remains glaringly white: In 2018, the AIA estimated that its membership was only 2% Black.

Working against Williams’ legacy was also the nature of his designs. The architect never settled on an identifiable style — drawing from Georgian, Spanish, Colonial and other traditional revival styles that didn’t square with the orthodoxies of 20th century European Modernists who dominated academic architectural narratives. “It’s about who is doing the remembering,” says Brooks, “and who is empowered to be doing the remembering.” In recent years, there have been some shifts in that power — with more Black scholars ascending to key positions at Los Angeles institutions. That includes Brooks, who was appointed to the Getty Research Institute’s curatorial team in 2019, as well as Milton Curry, who has served as dean of the USC School of Architecture since 2017, and who helped orchestrate the acquisition of Williams’ papers. (Williams was a USC alum.)

Hudson, who has written the few books available on her grandfather’s work, including 2012’s “Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style,” had spent years trying to place the archive. Some institutions wanted only pieces of it; others, nothing at all. “I’ve been on sort of a 30-year journey on deciding where it was going and what was happening with it,” she says. “I got a lot of people telling me they weren’t interested.”

To Hudson’s credit, she was undeterred. “I wanted to honor my grandfather and hopefully put his work in a position to be respected,” she says. “He was so much more than ‘architect to the stars.’” Indeed, the archive will allow scholars and critics to begin to consider Williams’ architecture in a methodical way. It also will be critical to shaping future generations of architects. “We’re now in a renaissance of Black American contemporary artists — many of whom were educated through the prism of a very robust period of cultural history and identity scholarship,” says Curry. “Architecture does not have that lineage, nor history. There are so few Black architects, architectural theorists and historians. The few that we have need to be studied and understood.”

To consider Williams’ work is to consider the lives of a postslavery generation shaped by segregation, the civil rights movement and various civil uprisings. It is also to consider the peculiar position of Los Angeles, where the codes that governed race were just loose enough to let a Black architect triumph. In the life of one man lie all the contradictions and the struggles of American history, says Brooks. “You can trace the history of democracy through the story of Paul Williams.”

Paul R. Williams faced the challenge of designing buildings while navigating the racial complexities of Los Angeles.(Julius Shulman / J. Paul Getty Trust)

Williams’ Awards

- 1923 – First African-American member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA)

- 1939 – AIA Award of Merit for the design of the MCA Building in Los Angeles

- 1941 – Lincoln University of Missouri Honorary Doctor of Science

- 1951 – Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., Man of the Year award

- 1952 – Howard University Honorary Doctor of Architecture

- 1953 – NAACP Spingarn Medal for outstanding contributions as an architect and member of the African American community

- 1956 – Tuskegee Institute Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts

- 1957 – First black member to be inducted into the AIA’s College of Fellows

- 2017 – Posthumously honored with the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Gold Medal

Williams’ commercial buildings are just as recognizable as his commissioned mansions. From the LAX Theme Building, the LA County Courthouse, Saks Fifth Avenue, the Palm Springs Tennis Club, Perino’s, the Ambassador Hotel, the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, and the Music Corporation of America building in Beverly Hills to modest tract houses, apartments, hospitals, schools, hotels, churches, private clubs, public housing projects, department stores, funeral homes and even car dealerships, Williams made his mark on the city of Los Angeles and the world of commercial architecture.

And while high society was aware of and applauded his talents, he never forgot about his community and his upbringing. Williams designed the Nickerson Garden Housing Project, the Pueblo del Rio Housing Project, the 28th St. YMCA, the First AME Church, much of the West Adams neighborhood and the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, one of the few institutions that would insure blacks at a time when other businesses would charge outrageous premiums or flat-out deny them coverage.

Williams passed away in 1980, and even in death was dealt a final reminder that race in America is still a complex and pressing issue: His career archives—containing his drawings, photos, business records, writings and notes—were destroyed when the Broadway Federal Savings building in Watts burned down in the civil unrest of the 1992 LA riots after police officers were acquitted in the Rodney King verdict. VIA